This date was a double-header in the AutoFlick chronology. Upon arriving in Washington, DC, to go to the Poor People’s Campaign, Izzy and Speedy see a man throw a cigarette from his 1960 Fiat 1100.

This date was a double-header in the AutoFlick chronology. Upon arriving in Washington, DC, to go to the Poor People’s Campaign, Izzy and Speedy see a man throw a cigarette from his 1960 Fiat 1100.

“The 1100 was the upscale Fiat, not the cheapo shoebox on wheels, and yet clowns could have come pouring out of it at any minute. It was boxy, but smoothed on all its edges, with a brown panel running from the leading edge of the front door back to a modest fin. It had a dowdy shape saved by a streak of chrome along the flank that gave the car a forward lean, like it was going somewhere even when it was standing still.”

Later, Izzy and some new friends are picked up by the D.C. metro police and taken in their squad car, a 1965 Plymouth Fury, to the station house. Their crime? Wading in the Potomac.

I took off my sneakers and socks and arranged them with a Boy Scout’s sensibility, but I hesitated long enough over the waist button of my khakis that my momentum stalled. I leaned over and rolled my pant legs up above my calves and then yanked them as far as they would go toward my knees. She was bent over, rinsing her arms in the river and paying no obvious attention to me. In case you haven’t noticed, there is something about teenage girls in their underwear bent over.

The water was good. There was a gravel bar underfoot and the barely perceptible current gently washed between our legs. The kids dunked their heads in the water and started to splash one another. Suddenly the sky turned a shade or two clearer, and a lightness drifted from across the river like the first taste of something unbearably good that you knew would only come in small doses. Charlotte faced the direction from which the levitation came and arched her back, stretching her face into the fresher air, and raised her arms out straight from her shoulders, spreading sail to catch every square inch.

She was a skinny, sunburnt hillbilly with home-cut hair and tomboy muscles in well-worn, feed-store clothes, but there was a place in the pantheon of goddesses for her as well. I took off my shirt and tossed it onto the bank. I bent over and washed my arms and neck, and another freshet rolled across the river and upon us. She turned to face me as I waded to her and she reached toward me.

Clasping our hands, we slowly circled each other. The sky continued to lift, seeming to pull lightness up from the edges of the horizon. There were cars bustling across the bridge above us, but the sparrows in the trees were oblivious, pursuing their own agenda. I was looking into her face, but she was looking up into the sky.

A 1962 Olds 88 passes at high speed and flicks a cigarette to the road. Speedy tries to catch up but loses him. Then he gets the idea of marking cars that have already been cited in the study of people who flick cigarettes from automobiles.

A 1962 Olds 88 passes at high speed and flicks a cigarette to the road. Speedy tries to catch up but loses him. Then he gets the idea of marking cars that have already been cited in the study of people who flick cigarettes from automobiles.

Driving home from work, Izzy and Speedy come across a woman driving a 1963 Chevy Impala. She tosses her cigarette. When asked to explain why, she tells Izzy he’s too young to smoke.

Driving home from work, Izzy and Speedy come across a woman driving a 1963 Chevy Impala. She tosses her cigarette. When asked to explain why, she tells Izzy he’s too young to smoke. Izzy and Speedy confront a butt-flicker in a 1960 Chevrolet Apache on their way to work. It doesn’t go well.

Izzy and Speedy confront a butt-flicker in a 1960 Chevrolet Apache on their way to work. It doesn’t go well. Later, Izzy commits a hippie faux pas while riding with Juliana in a 1957 Dodge Regent to see the Fifth Dimension at the music circus outside of Lambertville.

Later, Izzy commits a hippie faux pas while riding with Juliana in a 1957 Dodge Regent to see the Fifth Dimension at the music circus outside of Lambertville. This date was a double-header in the AutoFlick chronology. Upon arriving in Washington, DC, to go to the Poor People’s Campaign, Izzy and Speedy see a man throw a cigarette from his 1960 Fiat 1100.

This date was a double-header in the AutoFlick chronology. Upon arriving in Washington, DC, to go to the Poor People’s Campaign, Izzy and Speedy see a man throw a cigarette from his 1960 Fiat 1100. Hitch-hiking home from work, Izzy gets a ride with girl from his high school who is driving her family’s 1959 Ford Fairlane Ranch Wagon. She throws her cigarette out the window as she rushes to make room for him in the front seat. It turns out better than he might have expected.

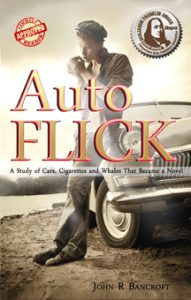

Hitch-hiking home from work, Izzy gets a ride with girl from his high school who is driving her family’s 1959 Ford Fairlane Ranch Wagon. She throws her cigarette out the window as she rushes to make room for him in the front seat. It turns out better than he might have expected. The design team at Ecphora Press has been hard at work on a new cover for AutoFlick. The impetus came from a discussion I had with someone who has a lot more experience in the book business than I do. Our conversation took place at the IBPA publishing conference back in April.

The design team at Ecphora Press has been hard at work on a new cover for AutoFlick. The impetus came from a discussion I had with someone who has a lot more experience in the book business than I do. Our conversation took place at the IBPA publishing conference back in April. I was cleaning out my cell phone because Apple had so helpfully notified me that I was running out of storage.

I was cleaning out my cell phone because Apple had so helpfully notified me that I was running out of storage.