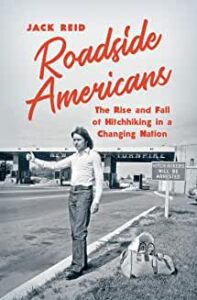

Jack Reid

University of North Carolina Press

A scholarly work examining how hitchhiking in America changed over a 60-year period as a result of shifting economic conditions and changes in social cohesiveness.

Reid delivers a thoroughly researched examination of hitchhiking in America through six periods in the 20th century. His work is based heavily on popular accounts published in newspapers and other periodicals. These sources include both opinion pieces and news articles, though the former seem to get more focus as one of the author’s goals is to map shifting popular opinion about hitchhiking.

There is an extensive bibliography of published books and film, though this seemed to get less attention in the text. The author does a good job describing the shifting political, economic and social context over the study period: 1928-1988.

Reid observes that economic conditions are a major factor in the popular acceptance of hitchhiking, both among those seeking rides and those giving them. In the Depression and during Word War II, fewer people had cars, so hitchhiking was more accepted. During periods of prosperity, hitchhiking is less popular – with the exception of the 1960s, when many young people took it up as a lifestyle choice.

Reid also notes that there were differing moral/social views of hitchhiking across all six periods. There always seem to be some people who think it reflects laziness and moral lapse. And there have always been supporters who see in the practice independence, self-reliance and willingness to engage with others. In prosperous times, the risks of hitchhiking take more weight.

These conclusions are intuitive enough, and the author asserts them over and over throughout the book. The conclusions seem obvious and their repetition gets tedious at times, at least for a lay reader. For anyone who grew up hitchhiking in the 1960s, this book will provide little new insight about the activity. It may be more useful for those who have never done put their thumb out for a ride, picked up a hitcher or been on the road during one of its heydays.

The book is greatly enhanced by photographs that appear to come from the public record. More would be better. The type is excruciatingly small. There is a typo on page 1, the worst place for it.

The narrative is strongest when Reid reports first-hand accounts by hitchhikers. And he ends with a tantalizing observation: that climate change and a reviving social consciousness may lead to a shift in public perception and renewed interest in hitchhiking.