Chapter 1. Jet lag.

The minute I saw those two women I figured they were trouble. Not that kind of trouble. The other kind, the somebody’s-going-to-get-hurt trouble.

Watching them in the waiting lounge at the domestic airport in Reykjavik, I took them as lesbians at first. The sultry, black-haired one with serious eyes was pulling money out of her wallet to pay for their beers at the snack bar counter. The athletic red-head was laughing too loud at some joke. Yeah, I thought, the dyke on the right usually pays.

It was somewhere around eight in the AM. I had flown all night from Baltimore and got no sleep even though I took my medication – two Sagamore manhattans in the BWI airport lounge – before departure. After landing in the predawn, stumbled through the various gates and bought a bus ticket from Keflavik to the old domestic landing strip right in Reykjavik, smaller than a lot of bus stations I spend the night in back in the States.

I watched them take down their beer breakfast and reconsidered. They aren’t queers, I thought. They’re having too much fun together. Unless this is their first go-round.

I went out to watch the lines form and dissolve at the one check-in counter as each flight assembled itself and took off to some nook or cranny in Iceland. Like geese waddling around with rolling suitcases and backpacks until one of them ups itself into the air and all the rest follow after, honking like there’s no tomorrow. One of these days, there won’t be. A model airplane hovered overhead.

I went out to watch the lines form and dissolve at the one check-in counter as each flight assembled itself and took off to some nook or cranny in Iceland. Like geese waddling around with rolling suitcases and backpacks until one of them ups itself into the air and all the rest follow after, honking like there’s no tomorrow. One of these days, there won’t be. A model airplane hovered overhead.

Man sitting next to me talking to his wife. Americans. He was rehearsing the schedule of activities they would have on their trip. Almost like he was talking to himself. Like a little kid rehearsing the adventures he was about to have. They had the same tour package I had, even to the point where I corrected him in my head when he mixed up the iceberg boat trip with the dog sledding. Hank, probably not his real name, was excited. His wife, a short blonde, was probably a dream when she was sixteen and was stuck since then with a weird Sandra Dee hairdo. There was an upturned curl on the top of her head, like her coif was waiting for a surfer to come along.

She didn’t seem to be responding to him. She was chewing gum and bobbing her lower right leg over her left knee with that distracted way some women have, like they’d rather be doing anything other than listening to the guy’s drivel.

Time moved slow. Not enough of it to go out in Reykjavik. And I’m beat. A flight to Kulisuk formed just before my flight to Ilulissat. Outdoor thrill-seekers with skis and monster snow boots, gear bags massive enough for a Tokyo salaryman’s bed chamber. Two American women getting on in years making friends with everybody and letting the world know they were going on an honest dog-sledding expedition, not a tourist thing, and the mostly younger people indulged them.

Finally, they all tromped through the international security check which from where I sat looked seemed to take place in a closet and then it was just us waiting on the 11:45 to Ilulissat. The last flight until later in the afternoon. Once we were safely off, the check-in counter would close and, I’m guessing, so would the snack counter.

A short gray-haired woman who I later learned was from Pittsburgh. Intensely focused on the goings-on, asking questions at the counter, checking and re-checking her paperwork. Two Indian people who turned out to be from Chicago. Various Danes. None of them particularly great.

I checked in. They put a tag on my bag. Since they were only processing one flight at a time, I wondered how anything could get misplaced. Went through security, which was in closet with a door at each end, and out to the boarding-area waiting room. About the size of a small Dairy Queen. Bought a bottle of vodka in the duty free.

A Danish couple with a teenage girl. He’s got a friendly face and a Euro way of ignoring his wife or taking her for granted. She’s blonde and prototypically sweetly beautiful, blue eyes and honey-toned Scandinavian complexion.

Finally, we are directed through the boarding gate and outside. It’s Reykjavik cool, the sun breaking through, and it feels great to be outside again and walking along a string of turbo jets until we get to ours and climb aboard. I’m in the back. The Danes are behind me, There’s a truly lesbian couple further ahead in the cabin. Hank and Sandra Dee are just a row or two ahead, across the aisle.

Finally, we are directed through the boarding gate and outside. It’s Reykjavik cool, the sun breaking through, and it feels great to be outside again and walking along a string of turbo jets until we get to ours and climb aboard. I’m in the back. The Danes are behind me, There’s a truly lesbian couple further ahead in the cabin. Hank and Sandra Dee are just a row or two ahead, across the aisle.

We roll down the runway, the stewardess addresses us in Icelandic, I think, which nobody speaks, but it’s their airline, and then in English, which all the Danes seem to get. It’s a spunky little Bombardier Q200, only 19 passengers, but able to carry a lot of cargo and, more importantly, land on short, dicey airstrips. And usually there aren’t more than 19 people at a time interested in going to Greenland.

Reykjavik disappears under our wing and we are off into the North Atlantic and soon over the clouds and I blissfully drift to sleep. Totally missed the beverage service.

Woke up still over clouds, but the watch tells me we must be getting close to Greenland. Or over it. Still, those props keep spinning, driving air into the jets. We are a somewhat dumpy and middle-aged goose floundering north of the polar circle. Fully of jolly vacationers.

Sandra Dee has moved to the seat behind Hank and is leaning over, embracing him from behind with the small matter of the seat separating him. The Danish family has split up across the five seats at the back of the plane. He’s alone by the starboard window, his feet up on the seat next to him. The wife and daughter are a world apart, looking out the window behind me.

There are a few splotches of something below the wing. Far below, the Greenland ice cap. Undulating whites. Then more obvious changes in the terrain, even something like a mountain or ridge, still buried in white. And then more breaks through the clouds and a ravine or two and enough clues to sense that the landscape below is falling, sloping down toward the west coast of Greenland.

Suddenly, there is water below and ice floes or ice bergs in a gray-blue sea. In a few minutes, the landing gear deploy while we are still over the sea and the juxtaposition is one I have never seen before, a possibility that we would try to land on chunks of ice in a frigid Arctic sea with rubber tires. This throws me for a moment.

Then there is snow again beneath us, and suddenly closing down, and landscape rushing past and we’re getting closer and that goddamn tarmac has got fucking ice on it dude, what are you thinking, but the pilot takes us down on the lethal frozen landing strip and it doesn’t make even the littlest damn difference. We do not slide suicidal into a cliff or explode into a storage tank of aviation fuel. Instead, we manage to brake and come to a tidy halt because that’s what our stubby Q200 was designed to do before it makes a clever pirouette at the end of the short runway in Ilulissat. A jaunty short taxi out of harm’s way toward the terminal.

It’s cloudy and sort of snowing. It takes only a few minutes for the props to shut down and the door opens and the steps take you right down onto the tarmac swirling in cloudy snow. Ilulissat, the terminal exclaims. The six aircraft in the Air Iceland Connect fleet are each named for famous women in the settlement of Iceland, when Vikings who felt there was little opportunity left in Norway headed west into the sea. Ours is named for Aud the Deep-Minded, who captained a ship of 20 men and when they got to Iceland rewarded them with their freedom and gave them land.

It’s cloudy and sort of snowing. It takes only a few minutes for the props to shut down and the door opens and the steps take you right down onto the tarmac swirling in cloudy snow. Ilulissat, the terminal exclaims. The six aircraft in the Air Iceland Connect fleet are each named for famous women in the settlement of Iceland, when Vikings who felt there was little opportunity left in Norway headed west into the sea. Ours is named for Aud the Deep-Minded, who captained a ship of 20 men and when they got to Iceland rewarded them with their freedom and gave them land.

By the way, it’s incredibly cold. Below zero cold.

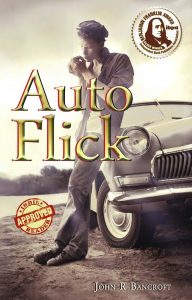

Speedy makes his first “I Flick Butts” bumper sticker and places it on a 1967 Plymouth Valiant.

Speedy makes his first “I Flick Butts” bumper sticker and places it on a 1967 Plymouth Valiant. A man driving a 1963 Rambler Ambassador throws his cigarette onto the road. Speedy runs him down, knowing the butt-flicker is the owner of the newspaper where he works.

A man driving a 1963 Rambler Ambassador throws his cigarette onto the road. Speedy runs him down, knowing the butt-flicker is the owner of the newspaper where he works. Riding home with his mother from work, Izzy spots a butt-flick from a 1964 Volkswagon bus. In Thailand, the air force was dropping flowers and popcorn from airplanes to celebrate the adoption of a new national constitution. When they get home, Speedy is excited about a constitutional argument about the legal standing of trees.

Riding home with his mother from work, Izzy spots a butt-flick from a 1964 Volkswagon bus. In Thailand, the air force was dropping flowers and popcorn from airplanes to celebrate the adoption of a new national constitution. When they get home, Speedy is excited about a constitutional argument about the legal standing of trees. June 16, 1968, was Father’s Day.

June 16, 1968, was Father’s Day. Izzy and Speedy follow a kid in a 1957 Buick LeSabre who is looking for a way out of the draft. They end up at a Quaker meeting.

Izzy and Speedy follow a kid in a 1957 Buick LeSabre who is looking for a way out of the draft. They end up at a Quaker meeting. June 7, 1968, is the first day of the AutoFlick story. Izzy and his father see two kids in a 1965 Triumph Spitfire throw cigarette butts into the road. They follow them to a gas station.

June 7, 1968, is the first day of the AutoFlick story. Izzy and his father see two kids in a 1965 Triumph Spitfire throw cigarette butts into the road. They follow them to a gas station. And I’ve retooled my online sales strategy. For two years, I have watched in frustration as Amazon sellers undercut the $16 retail price. Within a week after the book was first published, someone was selling a “used” copy for $11. Now, there are people offering the book for $2.

And I’ve retooled my online sales strategy. For two years, I have watched in frustration as Amazon sellers undercut the $16 retail price. Within a week after the book was first published, someone was selling a “used” copy for $11. Now, there are people offering the book for $2.

Suddenly there is no one near the Icefjord sign and I realize the Dachshund-size baggage claim belt has already delivered its goods and there is my bag, forlornly waiting for me. Together, we roll outside where the Icefjord van is quickly filling up. It’s down to an Italian couple and me for the last seat in the van.

Suddenly there is no one near the Icefjord sign and I realize the Dachshund-size baggage claim belt has already delivered its goods and there is my bag, forlornly waiting for me. Together, we roll outside where the Icefjord van is quickly filling up. It’s down to an Italian couple and me for the last seat in the van. We drive to the starting point of the hike in another rundown minivan that keeps the tourist industry humming in Ilulissat.

We drive to the starting point of the hike in another rundown minivan that keeps the tourist industry humming in Ilulissat. The guide explains that the third wave of native people, the Thule, lived here as late as 1850, when they were lured away to the comforts of European living in Ilulissat, then going by its Danish name.

The guide explains that the third wave of native people, the Thule, lived here as late as 1850, when they were lured away to the comforts of European living in Ilulissat, then going by its Danish name. I went out to watch the lines form and dissolve at the one check-in counter as each flight assembled itself and took off to some nook or cranny in Iceland. Like geese waddling around with rolling suitcases and backpacks until one of them ups itself into the air and all the rest follow after, honking like there’s no tomorrow. One of these days, there won’t be. A model airplane hovered overhead.

I went out to watch the lines form and dissolve at the one check-in counter as each flight assembled itself and took off to some nook or cranny in Iceland. Like geese waddling around with rolling suitcases and backpacks until one of them ups itself into the air and all the rest follow after, honking like there’s no tomorrow. One of these days, there won’t be. A model airplane hovered overhead. Finally, we are directed through the boarding gate and outside. It’s Reykjavik cool, the sun breaking through, and it feels great to be outside again and walking along a string of turbo jets until we get to ours and climb aboard. I’m in the back. The Danes are behind me, There’s a truly lesbian couple further ahead in the cabin. Hank and Sandra Dee are just a row or two ahead, across the aisle.

Finally, we are directed through the boarding gate and outside. It’s Reykjavik cool, the sun breaking through, and it feels great to be outside again and walking along a string of turbo jets until we get to ours and climb aboard. I’m in the back. The Danes are behind me, There’s a truly lesbian couple further ahead in the cabin. Hank and Sandra Dee are just a row or two ahead, across the aisle. It’s cloudy and sort of snowing. It takes only a few minutes for the props to shut down and the door opens and the steps take you right down onto the tarmac swirling in cloudy snow. Ilulissat, the terminal exclaims. The six aircraft in the Air Iceland Connect fleet are each named for famous women in the settlement of Iceland, when Vikings who felt there was little opportunity left in Norway headed west into the sea. Ours is named for Aud the Deep-Minded, who captained a ship of 20 men and when they got to Iceland rewarded them with their freedom and gave them land.

It’s cloudy and sort of snowing. It takes only a few minutes for the props to shut down and the door opens and the steps take you right down onto the tarmac swirling in cloudy snow. Ilulissat, the terminal exclaims. The six aircraft in the Air Iceland Connect fleet are each named for famous women in the settlement of Iceland, when Vikings who felt there was little opportunity left in Norway headed west into the sea. Ours is named for Aud the Deep-Minded, who captained a ship of 20 men and when they got to Iceland rewarded them with their freedom and gave them land.